2D Approximation of the step-to-step map

Most bipedal systems are underactuated at the ankle joint because their actuators are not strong enough to counteract the weight of the robot and because the foot starts to rotate when the COM falls outside of the base of support at the foot. This poses a challenge to locomotion that humans and other bipedal animals have been able to overcome by “falling controllably”. Walking is in essence falling while breaking the fall by placing the foot in front. Robotic mechanisms seeking to mimic this walking method must understand the dynamics of the system which can be done by integrating the equations of motion much like is done with simulators. Integrating EOM from one instance of a gait cycle to the next as a function of current states and control inputs yields a Poincare map.

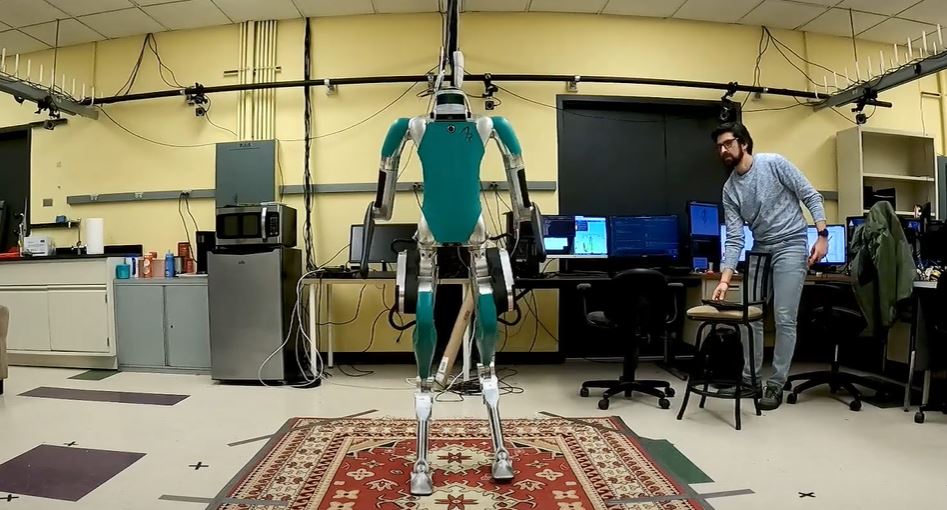

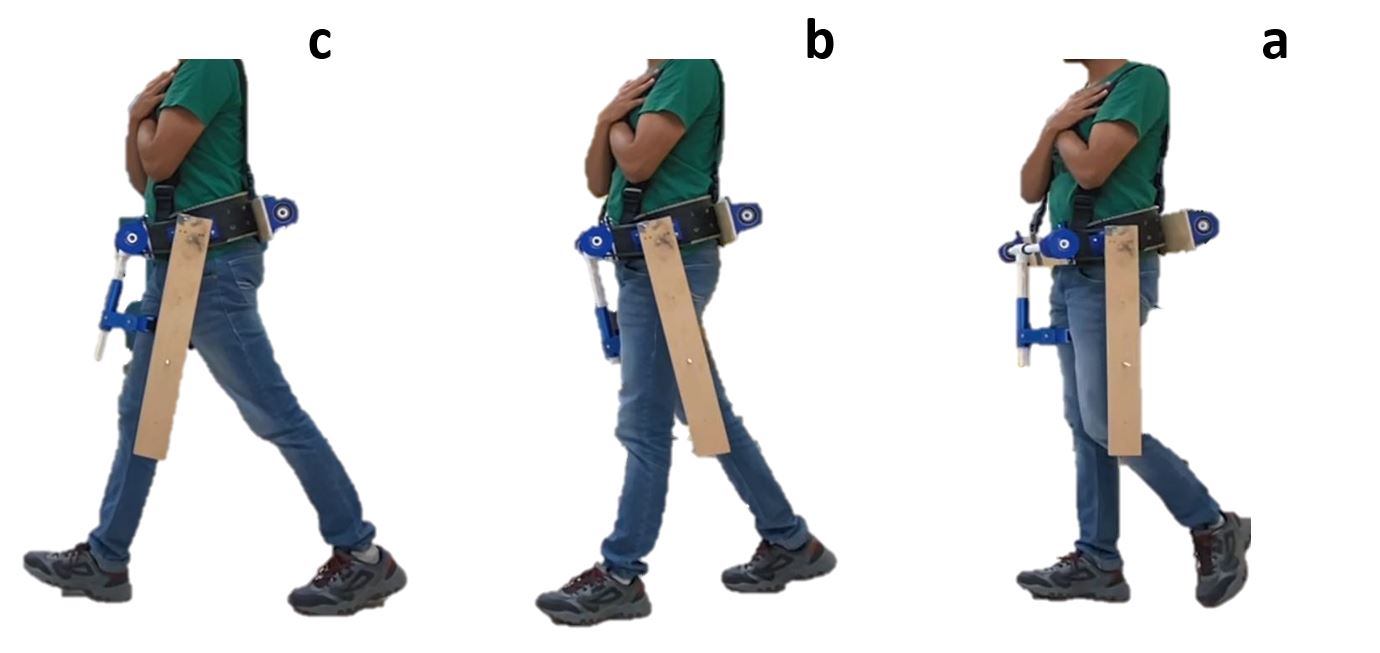

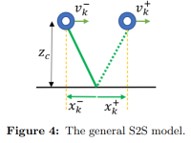

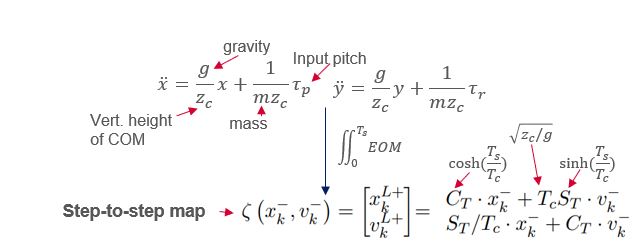

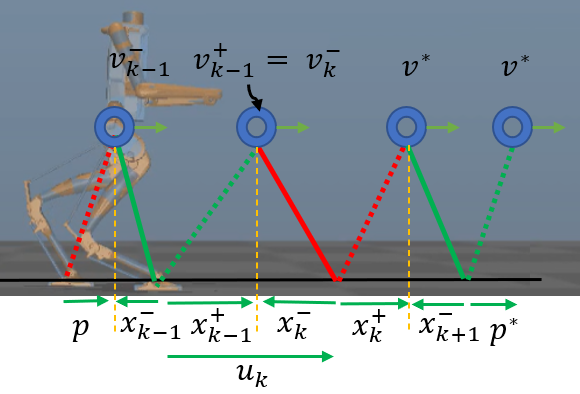

The drawback of numerically solving for the Poincare map is that it slows down the computation. One alternative solution is using a simplified model. We used the LIPM to simplify the robot dynamics and develop a stepping controller for Digit. The equations of motion of the inverted pendulum become linear by keeping the vertical height of the mass constant. Integrating the EOM gives a S2S map, also known as the Poincare map.

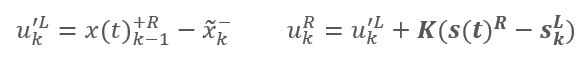

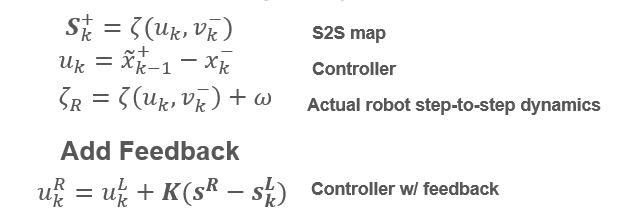

By choosing a constant stepping frequency, we can use the S2S map to solve for the foot placement required to achieve the desired velocity or position of the COM wrt the stance foot at foot strike. The S2S map is reformaulated such that the control input is step length (u). A feedback term is introduced making the controller a discrete controller with feedback. Gains can be tuned such that the system reaches orbital stability.

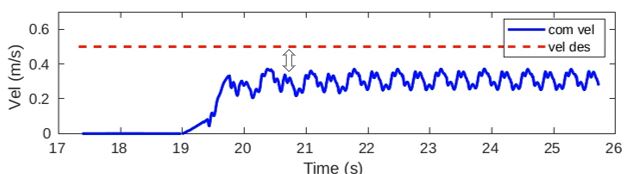

One major drawback from using the simpplified model dynamics of the LIPM is that there might be a steady-state error that arises due to the dynamic differences between the LIPM and robot dynamics.

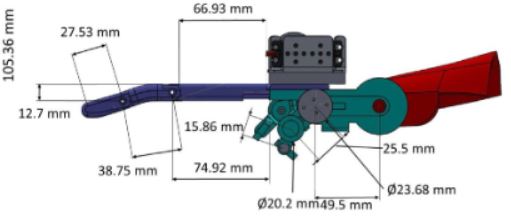

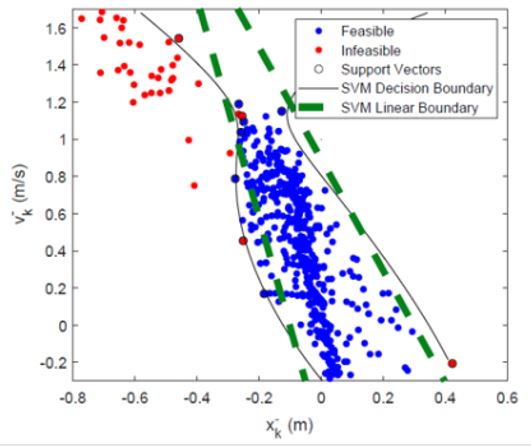

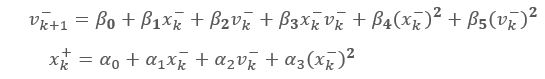

An alternative way of extracting the S2S dynamics of the system is by capturing the dynamics of certain points of interest such as COM position and velocity and using them as Poincare map parameters. We ran physics simulations of the system walking under LIPM-based stepping and collected waveform kinematic data. The data was converted into point-of-interest data as function of controller inputs. The points of interest are then run through a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier where we use the classification hyperplane equation to classify the data as either feasible or infeasible. Basically, separating data for which the robot succesfully takes a step and when the robot falls or slips. The feasible data is then fitten to a function using polynomial regression. This function is now an analytical version of the Poincare map equation.

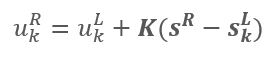

The feasible data was fitted to an analytical polynomial S2S map shown below. A discrete and non-linear controller was formulated. The error S2S dynamics were linearized about an equilibrium point and the gain K was solved for such that the system became asymptotically stable.

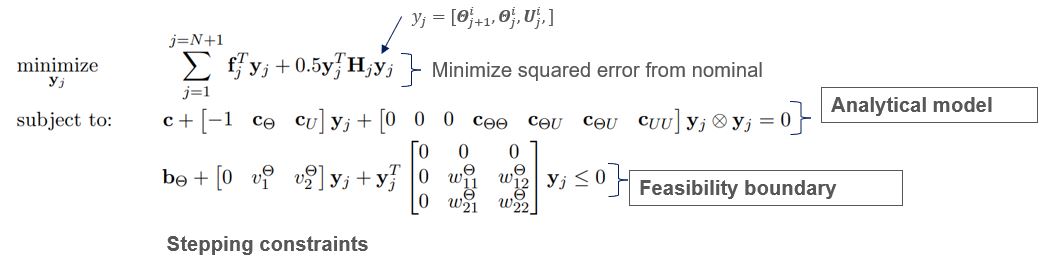

Having such types of analytical maps and analytical boundaries allows the formulation of an optimization problem that can be used to optimize foot placement to achieve desired walking speed, recover from a fall, or walk through a constrained environment. The best part is that these analytical models are typically of low order and can be solved for very fast for real-time control.

QCQP implementation:

A foot strike corrected stepping controller was also implemented to account for interstep disturbances that may occur during walking.